Noemi S. Conan

Biography

Noemi S. Conan (b. 1987, Poland) currently lives and works in London. She is studying at The Royal College of Drawing, London and previously studied Painting and Printmaking BA (Hons) at Glasgow School of Art, 2021 and at Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst, Leipzig in the class of Professor Christoph Ruckhäberle.

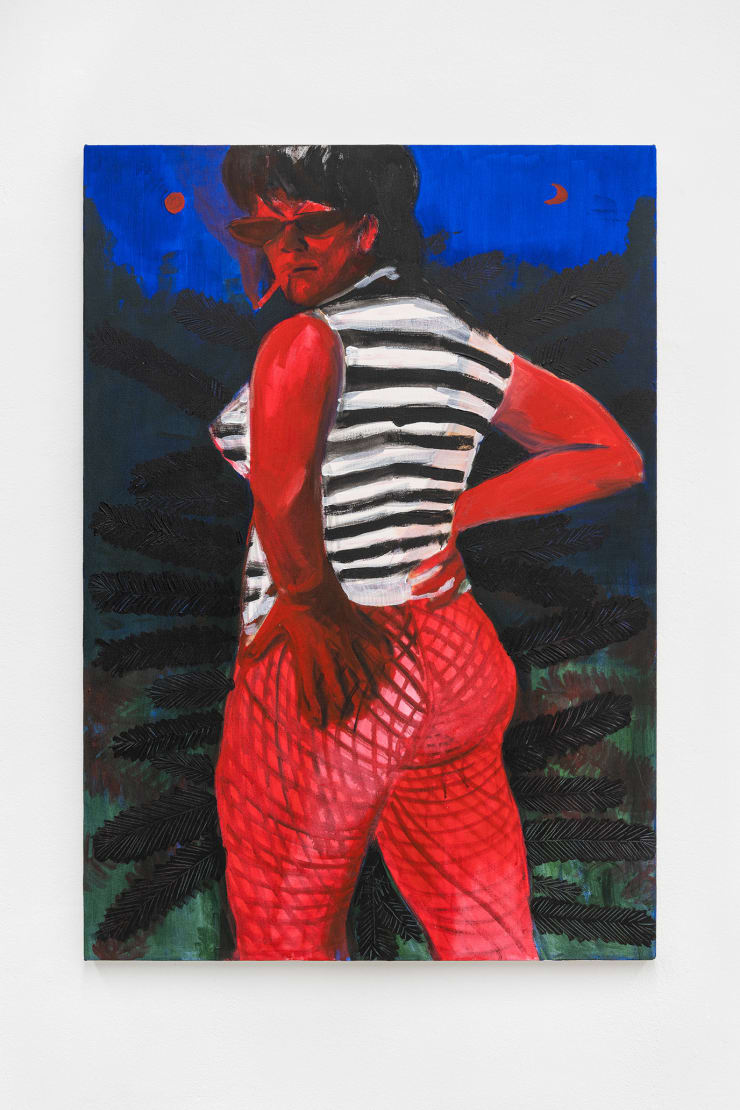

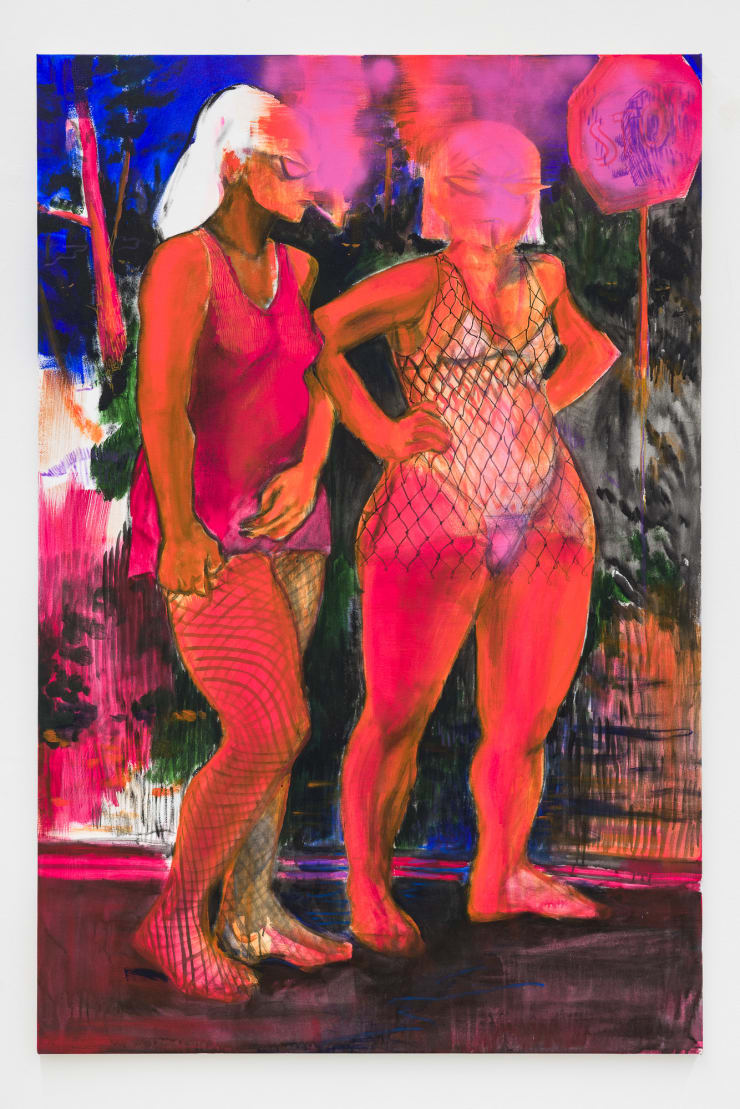

Conan’s practice uses folkloric female figures of Rusalki to “explore, recall and share half-remembered icons of a post-communist youth”. Rusalka are a feminine entity in Slavic folklore which, before the 19th century, were not considered evil but rather a remnant of pagan mythology which linked them with fertility. However, since the 19th century they have been decidedly demoted from the goddesses they once might have been and are frequently associated with malicious and predatory intent. The tale is that these women deviated or violated social norms, such as pre-marital pregnancy, abandoning husbands or suicide, and have become outcast spirits within a purgatory realm. This manifests in their punishment of roaming the earth in eternal youth with one another, preying on mankind and exhausting their victims to death and corruption through dance and laughter (a factor Conan struggles to view as a punishment and not an especially successful deterrent).

However, within this, the backstory of the Rusalki and their fall from grace is often interlaced with forms of mistreatment from men: a woman who committed suicide due to an unhappy marriage, were jilted at the alter or abused and harassed by their much older husbands. Thus, there is the ambiguity concerning their nefarious nature in contradiction to what, at least through a contemporary lens, is a rather sympathetic narrative. Alongside this, the folk tales of Rusalki often possess a strong redemptive arc such as in To lubię by the Polish Romantic-era poet Adam Mickiewicz where the protagonist walks alone in the countryside when he gets accosted by a Rusalka who attacked from under a bridge. However, the poet is in such a state of malaise that the event excites him, causing the Rusalka to be both so confused and flattered that she decides not to kill him, which in turn allows for her own redemption and ascension into heaven.

This folkloric backdrop to Conan’s work is layered by her early memories of Post-Soviet sex workers appearing in the neighbourhood around her and who at the time she believed were Rusalki with their glamourous revealing outfits, leather boots and uncompromising demeanour. The combination of influences creates a figurative manifestation of a style of unapologetic modern woman. As Conan states:

“The women I paint- somewhere between a girlboss and Stakhanovite worker with a pinch of Slavic folklore for flavour- both confront the viewer and maintain their cool disregard to appeal to any sensibilities whatsoever. They will not provide an explanation, no comforting smile- that comes at extra cost and you can't afford it. Customer service has yet to be invented and nobody is in a rush to look bothered. A narrative of cigarette breaks, sunburn and inappropriate clothing between a roadside and a primordial forest. Foragers in polyester, plastic debris, blinking rear lights. Boredom as revolution. Countries of the old Eastern Block as edge lands, haunted by modern wild women. Feral femininity, disruptive disinterest. Hauntological woodland sprites. The social margins in their full monumental frenzy, larger than life and sparing nobody. Aggressive passivity and violent avoidance.”

Exhibitions

Works

-

Noemi S. ConanGot A Light?, 2021Acrylic on canvas180 x 120 cm

Noemi S. ConanGot A Light?, 2021Acrylic on canvas180 x 120 cm

70 7/8 x 47 1/4 in -

Noemi S. ConanHere's Looking At You, 2021Acrylic paint and varnish on canvas50 x 40 cm

Noemi S. ConanHere's Looking At You, 2021Acrylic paint and varnish on canvas50 x 40 cm

19 3/4 x 15 3/4 in -

Noemi S. ConanHide and Seek, 2021Acrylic paint and varnish on canvas65 x 65 cm

Noemi S. ConanHide and Seek, 2021Acrylic paint and varnish on canvas65 x 65 cm

25 5/8 x 25 5/8 in -

Noemi S. ConanJuicy, 2021Acrylic on canvas120 x 85 cm

Noemi S. ConanJuicy, 2021Acrylic on canvas120 x 85 cm

47 1/4 x 33 1/2 in -

Noemi S. ConanMidnight Swim, 2021Acrylic on canvas100 x 130 cm

Noemi S. ConanMidnight Swim, 2021Acrylic on canvas100 x 130 cm

39 3/8 x 51 1/8 in -

Noemi S. ConanSentinels, 2021Acrylic and spray paint on canvas180 x 120 cm

Noemi S. ConanSentinels, 2021Acrylic and spray paint on canvas180 x 120 cm

70 7/8 x 47 1/4 in

Installation shots

Publications